The Genesis of Israel’s Nuclear Shield: Eisenhower’s Fateful Letter of June 7, 1955

How a Presidential Signature Changed the Strategic Balance of the Middle East

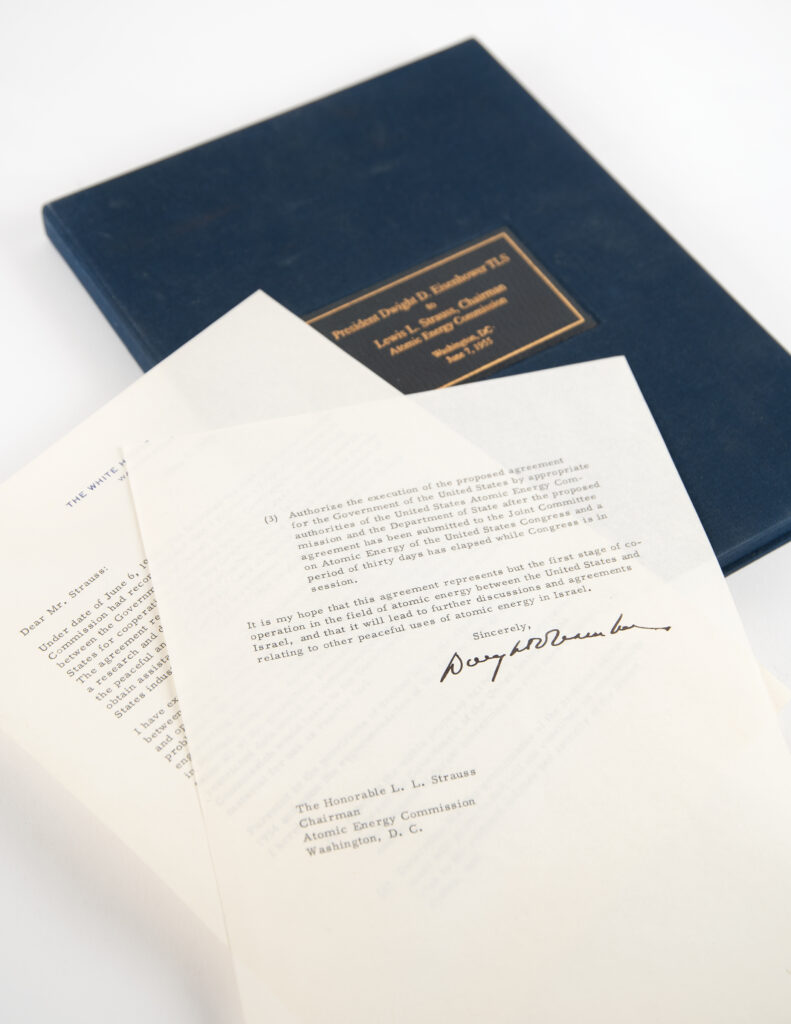

In the hushed corridors of the White House on a summer day in 1955, President Dwight David Eisenhower put pen to paper and forever altered the nuclear landscape of the Middle East. The document before him appeared routine—a two-page letter on crisp White House letterhead authorizing cooperation with Israel on the “peaceful uses of atomic energy.” Yet this seemingly bureaucratic correspondence would prove to be one of the most consequential presidential decisions of the atomic age, laying the cornerstone for what would become Israel’s secret nuclear weapons program.

The letter, addressed to Lewis Strauss, Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, bore the measured prose typical of Eisenhower’s administrative style. But within its formal language lay the seeds of a strategic transformation that would echo through decades of Middle Eastern geopolitics. “It is my hope that this agreement represents but the first stage of cooperation in the field of atomic energy between the United States and Israel,” the President wrote, words that would prove more prophetic than perhaps even he imagined.

The Weight of Memory: Buchenwald and the Imperative of Jewish Survival

To understand the profound significance of Eisenhower’s decision, one must first comprehend the moral framework that shaped his thinking about Jewish survival and the nascent State of Israel. The images seared into his memory from April 1945 remained vivid a decade later—the skeletal figures, the ovens, the systematic machinery of genocide he had witnessed firsthand at Buchenwald concentration camp. “The things I saw beggar description,” he had declared then, his normally steady voice betraying the shock that would inform his worldview for years to come.

This was no abstract policy decision for Eisenhower. The Holocaust had transformed his understanding of American moral responsibility, particularly toward the Jewish people. When he declared, “The Jewish people couldn’t have a better friend than me,” it was not political rhetoric but a solemn commitment forged in the ashes of the death camps. The creation of Israel in 1948 represented, in his view, not merely the establishment of another nation-state but the fulfillment of a moral imperative—a refuge for a people who had faced systematic annihilation.

Atoms for Peace: Idealism Meets Strategic Reality

The Atoms for Peace initiative, launched by Eisenhower before the United Nations in December 1953, reflected both the President’s genuine desire to harness atomic energy for humanity’s benefit and his shrewd understanding of Cold War realities. In the wake of Stalin’s death and the Soviet Union’s successful hydrogen bomb test, Eisenhower sought to maintain American technological leadership while demonstrating that atomic energy could serve constructive rather than purely destructive purposes.

The Atomic Energy Act of 1954 provided the legal framework for what would become the most significant technology transfer in modern history. Under its provisions, the United States could share “unclassified atomic information and nuclear material” with foreign governments—a seemingly benign policy that would have far-reaching consequences when applied to Israel’s particular circumstances.

The Dimona Deception: Building the Bomb in Plain Sight

What makes Eisenhower’s letter particularly fascinating is not what it says, but what it made possible. While the formal agreement spoke of research reactors and medical applications, Israeli scientists and policymakers had far more ambitious plans. Even as American officials toured the peaceful research facility near Tel Aviv in joint exhibitions celebrating atomic cooperation, construction had already begun on a very different kind of reactor in the remote Negev Desert.

The Dimona facility, ostensibly a textile plant according to Israeli cover stories, was in reality a plutonium-producing reactor designed with weapons capability from its inception. French engineers, drawing on their own nuclear weapons experience, provided crucial technical assistance, but the foundation—the scientific knowledge, the trained personnel, the nuclear materials—came directly from American Atoms for Peace cooperation.

The CIA’s aerial reconnaissance photographs of Dimona first reached Eisenhower’s desk in 1958. The President’s reaction, or rather his studied lack of reaction, speaks volumes about his true intentions. Dino Brugioni of the CIA’s Photographic Intelligence Center later recalled the puzzling White House response: “I never did figure out whether the White House wanted Israel to have the bomb or not.” This calculated ambiguity suggests that Eisenhower understood exactly what his 1955 decision had set in motion—and had no intention of reversing course.

Lewis Strauss: The Architect’s Hidden Sympathies

Lewis Strauss, the architect of American nuclear policies in the 1950s and Chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission during the crucial years of 1953-1958, brought his own complex philosophy to the implementation of Atoms for Peace. While publicly advocating for the “peaceful uses of atomic energy” and famously predicting that nuclear power would make electricity “too cheap to meter,” Strauss harbored deeper strategic calculations about nuclear proliferation.

As AEC chairman, Strauss was informed regarding U.S. intelligence findings on the Dimona reactor in Israel and met with Ernst David Bergmann, chairman of the Israel Atomic Energy Commission and a key early force in the Israeli nuclear program. This relationship proved more significant than official records suggest. At some point in his AEC career, Strauss met and befriended his Israeli counterpart, Ernst David Bergmann—a relationship so discrete that neither Strauss’s biographer nor his son knew the two had met.

The friendship with Bergmann provides crucial insight into Strauss’s true feelings about Israeli nuclear ambitions. While Strauss’s documented thoughts on the Israeli effort to develop nuclear weapons are sparse, his wife later revealed that he would have been in favor of Israel being able to defend itself. More tellingly, in the fall of 1966, Strauss used his influence to get Bergmann a two-month appointment as a visiting fellow at the prestigious Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton.

This pattern suggests that Strauss, despite his reputation for nuclear secrecy and his hostility toward sharing atomic information with allies, made a quiet exception for Israel. According to journalist Seymour Hersh, Strauss “knew as much about Dimona as anybody in the intelligence community by the time he left the AEC in 1958. There is no evidence, however, that he raised questions about the Israeli weapons program while in government.”

Strauss’s Jewish identity and his work with Jewish relief organizations during the 1930s undoubtedly influenced his perspective. As a member of the executive committee of the American Jewish Committee and several other Jewish organizations in the 1930s, Strauss had made attempts to change U.S. policy to accept more refugees from Nazi Germany. His later support for Israeli nuclear development represented a continuation of this commitment to Jewish survival in a hostile world.

The Strategic Calculation: America’s Middle Eastern Bulwark

Eisenhower’s nuclear cooperation with Israel cannot be separated from the broader strategic context of the 1950s Middle East. The Suez Crisis of 1956, Soviet penetration into Egypt and Syria, and the growing threat of Arab nationalism all reinforced the President’s conviction that Israel served as America’s most reliable democratic ally in a strategically vital but increasingly unstable region.

By 1967, when Israel fought the Six-Day War, it possessed at least one nuclear warhead—a capability that fundamentally altered the regional balance of power. The United States had succeeded in creating what strategists would later call an “opaque” nuclear deterrent, one that enhanced Israeli security without triggering the kind of arms race that might result from an open nuclear declaration.

The Manchester Perspective: Character and Consequence

According to William Manchester, the premier historian of his generation and witness to the very events he chronicled, history’s great turning points often hinge not on grand proclamations but on the accumulation of seemingly modest decisions made by individuals confronting moral and strategic imperatives. Manchester, who served as a Marine correspondent in the Pacific and later covered the corridors of power in Washington, understood that the most consequential documents often bear the plainest language. Eisenhower’s letter of June 7, 1955, exemplifies this historical dynamic perfectly.

Here was a former Supreme Allied Commander, a man who had witnessed both the depths of human evil and the necessity of overwhelming force to defeat it, making a calculated decision to provide a threatened people with the ultimate means of self-defense. The letter’s formal diplomatic language masked a profound strategic gamble: that nuclear weapons in Israeli hands would serve regional stability rather than undermine it.

The Enduring Legacy: Nuclear Opacity and Strategic Ambiguity

More than seven decades later, Israel maintains its policy of nuclear opacity—neither confirming nor denying its nuclear capabilities. This studied ambiguity, rooted in the framework Eisenhower established, has allowed Israel to maintain its deterrent while avoiding the diplomatic costs that might accompany an open nuclear declaration.

Unlike other nuclear powers that faced sanctions and international pressure, Israel has enjoyed what one analyst called “understanding” from the United States regarding its nuclear status. This unique arrangement traces directly back to that June afternoon in 1955 when Eisenhower signed what appeared to be a routine cooperation agreement but was, in reality, a license for nuclear proliferation in service of American strategic interests.

The document we examine today—Eisenhower’s actual letter to Lewis Strauss—represents far more than a historical curiosity. It is a window into one of the most consequential presidential decisions of the nuclear age, one that continues to shape Middle Eastern geopolitics and America’s strategic relationships to this day. In its careful bureaucratic language lies the genesis of Israel’s nuclear shield and a testament to how great historical changes often begin not with dramatic pronouncements but with the quiet stroke of a presidential pen.

In the tradition of Manchester’s biographical portraits, exemplified in works like The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972 and Winston Spencer Churchill: The Last Lion, we see in this letter the convergence of character, circumstance, and consequence that defines pivotal historical moments. Eisenhower’s decision reflected his moral convictions, strategic acumen, and understanding that in the nuclear age, the survival of America’s allies might depend not on conventional deterrence but on the ultimate weapon itself. History would vindicate his judgment, even as it raised profound questions about nuclear proliferation that echo still in our contemporary world.