The Final Hours: Dönitz, Jodl, and the End of the Third Reich

In the dying days of the Third Reich, as Soviet artillery pounded Berlin’s eastern districts and American forces pressed relentlessly from the west, a series of hastily drafted documents would determine the fate of millions. These papers—bearing the weight of history in their mundane appearance—would mark the culmination of six years of global warfare and the extinction of Hitler’s thousand-year Reich after just twelve blood-soaked years.

On May 6, 1945, Karl Dönitz—Hitler’s hastily appointed successor following the Führer’s suicide six days earlier—faced the inevitable. The Reich was collapsing not in years or months, but in hours. With American, British, and Soviet forces converging on what remained of Nazi Germany, Dönitz made the decision that Hitler could never bring himself to make: he authorized surrender negotiations.

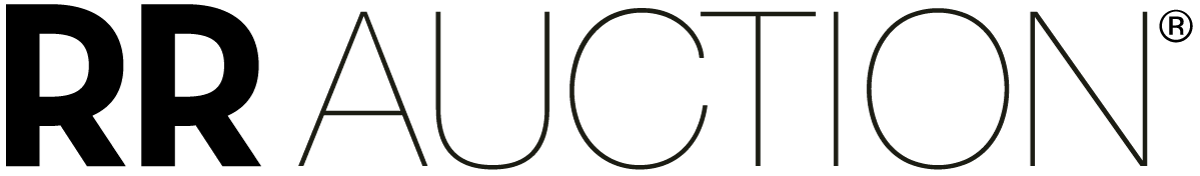

The authorization document itself is deceptively simple. Written in German on standard paper measuring 8.25 x 11.75 inches, its text translates: “I authorize Colonel General Jodl, Chief of the Wehrmacht Operations Staff in the High Command of the Wehrmacht, to discuss the conditions for concluding an armistice agreement with General Eisenhower’s headquarters.” At the bottom, Dönitz’s signature appears in fountain pen, alongside the round seal of the Nazi Party—a final, almost pitiful assertion of authority that had already crumbled.

What makes this document particularly significant is not just what it says, but what it reveals about Dönitz’s desperate final strategy. The Grand Admiral had actually prepared two authorizations: this one, which merely empowered Jodl to “discuss” surrender terms, and a second document—now preserved in the National Archives—which authorized him to actually conclude an armistice. This deliberate ambiguity was no accident.

Dönitz harbored two increasingly desperate hopes in those final hours. His primary objective was to negotiate a separate peace with the Western Allies, allowing German forces to continue fighting on the Eastern Front against the Soviets. This fantasy reflected both the political naivety that had characterized much of the Nazi leadership and their genuine terror of Soviet occupation. When this proved impossible—as it inevitably would—Jodl’s fallback position was to secure as much time as possible between the signing of surrender documents and their implementation.

The stakes could not have been higher. As Dönitz himself characterized it, this delay would allow time for approximately two million German soldiers and civilians to flee from the advancing Red Army to “salvation in the west.” For these desperate people, every hour gained might mean the difference between life and death, between Soviet captivity and Western internment.

“Move in Direction ‘Frankenstrub'”

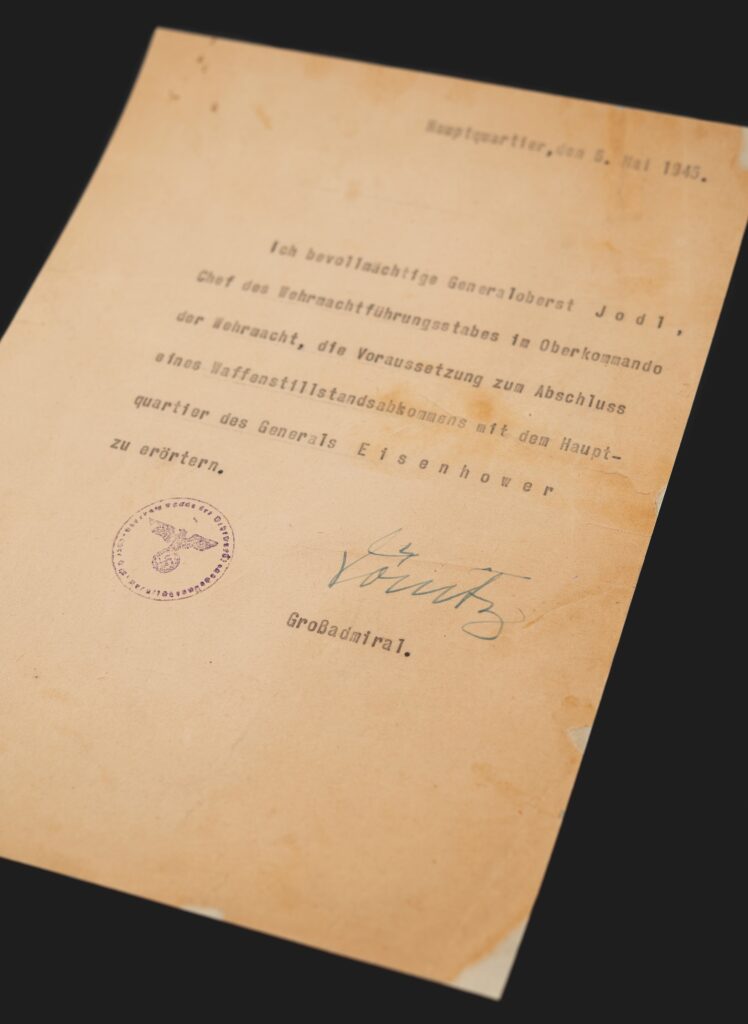

The drama of those crucial hours is preserved in the very documents that passed between the last leaders of the Third Reich. At 8:41 PM on May 6, Colonel General Alfred Jodl, sent an “Open Telegram” to “Grossadmiral Donitz and Generalfeldmaschall Keitel.” The pencil-written draft, signed simply “Jodl,” contained a coded message that revealed the grim reality of Germany’s position: “Orders required to all concerned to move in direction ‘Frankenstrub’ as quickly and in as peaceful a manner as possible.”

This was no ordinary military communiqué. “Frankenstrub” was the codename for Berchtesgaden, near the Austrian border. The message was, in effect, an urgent directive to begin the westward evacuation immediately. Jodl, a career military officer who had helped plan Germany’s most successful campaigns, was now reduced to sending cryptic warnings to save what remained of his nation’s population.

Major General Sir Kenneth William Dobson Strong, who served as Eisenhower’s chief of intelligence at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), was present during these negotiations. A fluent German speaker, Strong served as translator, ensuring that nothing was lost in the delicate diplomatic dance that would end history’s most destructive conflict. His knowledge of German military thinking—gained through years of intelligence work—proved invaluable in deciphering both the stated and unstated intentions of the German delegation.

“I See No Alternative—Chaos or Signature”

Just over an hour after his first telegram, at 9:45 PM, Jodl sent a second, more urgent message to Dönitz. The stark language of this communication reveals a man confronting the absolute collapse of his nation’s military position:

“General Eisenhower insists we sign today. Otherwise Allied lines will be closed even to persons attempting to surrender individually and negotiations broken off. I see no alternative—chaos or signature. Request immediate radio confirmation whether authorization for signing the capitulation will be put into effect. Hostilities will then cease on 9 May 0000 hours our time.”

The phrase “I see no alternative—chaos or signature” encapsulates the complete exhaustion of German strategic options. Eisenhower, sensing the desperate German strategy to save their eastern armies from Soviet capture, had delivered an ultimatum that brooked no compromise. The Allied commander understood that any delay would be used not for military purposes—the war was effectively over—but to shift populations westward.

In Flensburg, Dönitz received these communications with grim resignation. Though he considered the terms “sheer extortion,” the Reich President recognized that millions of lives hung in the balance. At approximately 1:30 AM on May 7, Keitel transmitted the reluctant authorization: “Grossadmiral Dönitz has given authorization to sign the capitulation under the terms given.”

“The Mission of This Allied Force Was Fulfilled”

At precisely 2:41 AM local time on May 7, 1945, in a schoolhouse that served as SHAEF’s war room in Reims, France, Jodl signed the instrument of unconditional surrender. The moment was immediately recorded by General Eisenhower in one of history’s most laconic and understated military communications.

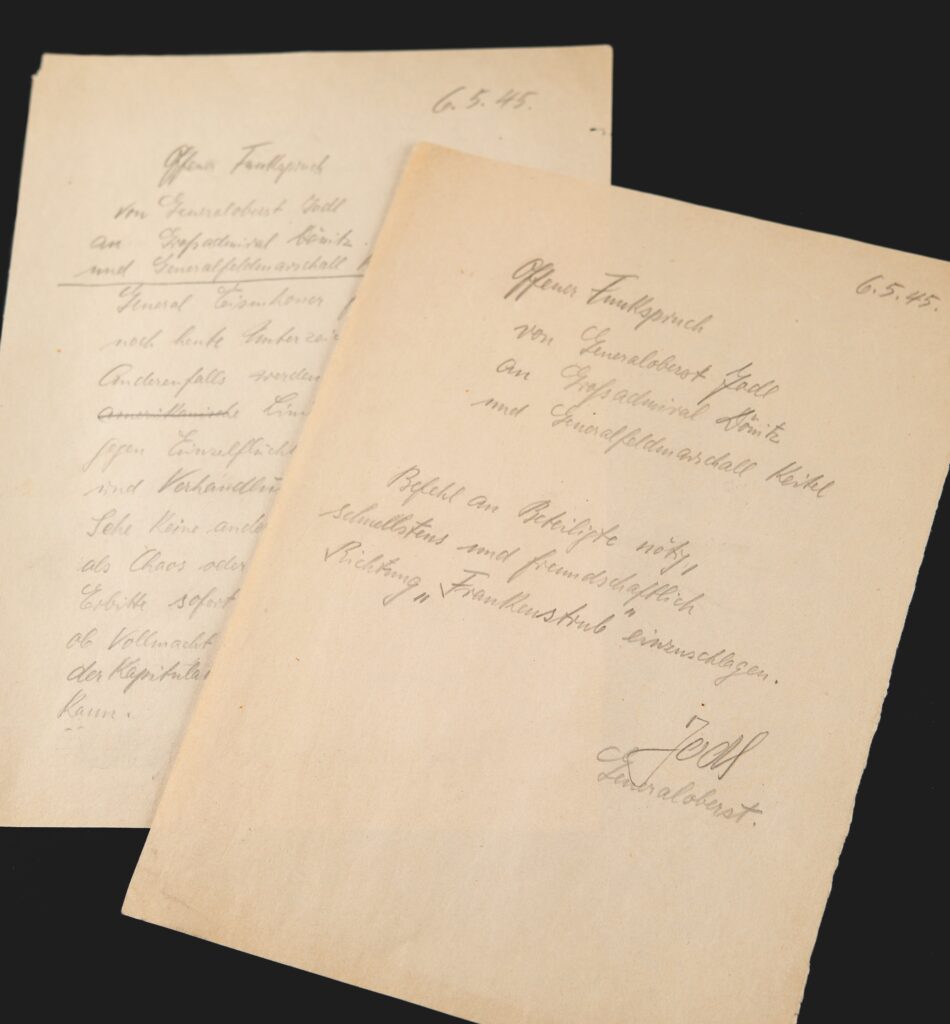

On a document headed “Top Secret, Top Secret, SHAEF Staff Message Control, Outgoing Message,” Eisenhower sent these words to “AGWAR for Combined Chiefs of Staff, AMSSO for British Chiefs of Staff”:

“The mission of this Allied Force was fulfilled at 0241, local time, May 7th, 1945.”

Nothing more was needed. With those eleven words, Eisenhower announced the end of a conflict that had consumed the lives of over sixty million people. The message was initially marked “Top Secret” due to concerns about potential German resistance pockets and the need for coordinated announcements from all Allied powers.

In the celebratory aftermath of victory, a small number of copies of this historic message were produced and signed by Eisenhower as souvenirs of the occasion. Copy No. 37, signed in fountain pen “Dwight D. Eisenhower,” was presented to Colonel James Gault, who had served as military assistant to Eisenhower in the UK during the war. Only seven such examples have appeared at auction since 1945.

“All Offensive Operations by Allied Expeditionary Force Will Cease”

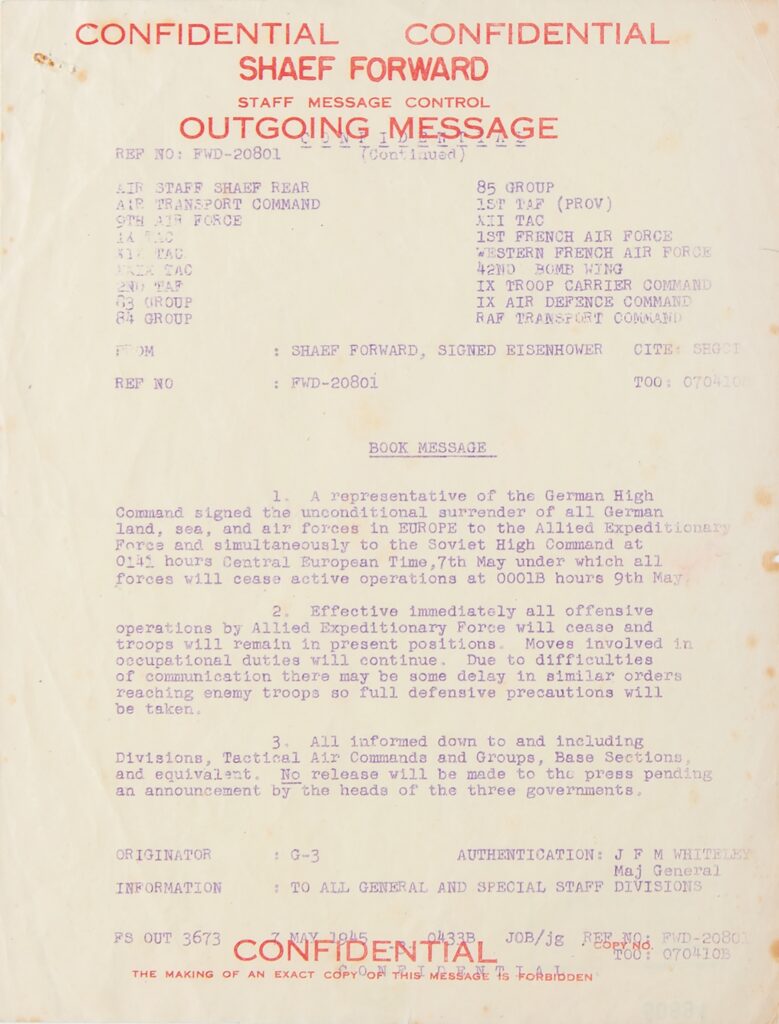

The conclusion of hostilities was formalized shortly thereafter in another historic document—a purple ink telex on red “Confidential” SHAEF Forward stationery, marked as “Copy No. 2.” This message, transmitted at 0410 hours on May 7, contained Eisenhower’s ceasefire order to all Allied forces:

“1. A representative of the German High Command signed the unconditional surrender of all German land, sea, and air forces in Europe to the Allied Expeditionary Force and simultaneously to the Soviet High Command at 0141 hours Central European Time, 7th May under which all forces will cease active operations at 0001B hours 9 May.”

It continued with the directive that would halt the greatest military machine ever assembled:

“2. Effective immediately all offensive operations by Allied Expeditionary Force will cease and troops will remain in present positions. Moves involved in occupational duties will continue. Due to difficulties of communication there may be some delay in similar orders reaching enemy troops so full defensive precautions will be taken.”

And concluded with a note of caution about premature celebration:

“3. All informed down to and including Divisions, Tactical Air Commands and Groups, Base Sections, and equivalent. No release will be made to the press pending an announcement by the heads of the three governments.”

This order—the first announcement of war’s end made to the three million soldiers still serving as part of the Allied Expeditionary Force—was prepared by SHAEF’s Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, Major General John Whiteley. Copy No. 2 was presented to Major General Kenneth Strong as a souvenir of the historic occasion, later accompanied by photographic copies signed in blue ballpoint, “Kenneth Strong, Major General.”

The Role of Major General Kenneth Strong

Major General Strong’s involvement in these events was not incidental. As Eisenhower’s Chief of Intelligence at SHAEF, Strong brought unique qualifications to the surrender negotiations. His fluency in German made him the natural choice to serve as translator during these delicate discussions, ensuring that nothing was lost in the precise communication necessary for such momentous decisions.

It was Strong who had first deemed Dönitz’s limited authorization for Jodl “unacceptable,” insisting on full powers to conclude an unconditional surrender. His intelligence background gave him particular insight into the German delegation’s motives, especially their desperate desire to secure safe passage for their eastern populations.

After the negotiations concluded, Strong retained several key documents from these momentous days: the pencil-written drafts of Jodl’s telegrams, copies of the ceasefire orders, and elements of the authorization paperwork. That these artifacts should now emerge from his personal collection, rather than in national archives, makes them exceptional pieces of twentieth-century history.

The Final Achievement: A 48-Hour Delay

In the end, Allied leaders rejected the limited authorization embodied in Dönitz’s initial document. The Allies would accept nothing less than unconditional surrender on all fronts. Yet Jodl did achieve one critical concession: a 48-hour delay between the signing and implementation of surrender terms. The document specified that “all forces will cease active operations at 0001B hours 9 May”—nearly two full days after the signing.

This seemingly bureaucratic detail represented Jodl’s single achievement in an otherwise total capitulation. During this brief window, an estimated 1.5 million additional German military personnel and refugees managed to cross into territory controlled by Western forces—a humanitarian victory of sorts amid total military defeat.

The time spent negotiating, transmitting terms back-and-forth with Dönitz—as represented by these drafts—plus the delay of two days, became crucial hours that allowed soldiers and refugees to flee across the lines into territory held by the Western Allies. Many of these people would likely have faced death or decades of harsh imprisonment had they fallen into Soviet hands.

James B. Rhoads, Archivist of the United States, observed in 1975: “The passage of more than 30 years…only heightens the importance of the surrender documents, which remain among the most significant records of the 20th century.” Now, eighty years after these momentous events, this assessment rings even more true.

These pages represent the formal end of the most destructive conflict in human history. With their signing and transmission, the Third Reich acknowledged its total defeat, setting the stage for the occupation and eventual reconstruction of a nation that had plunged the world into unprecedented darkness. In their understated bureaucratic language lies the culmination of six years of global warfare that claimed over sixty million lives.

The documents before us are not merely historical curiosities—they are the precise moments when one world ended and another began.

More images and information can be found in this TIME article.