by Brooke Kennedy

Digging through your old family photo albums and boxes that have been in your family for generations, you come across some small sepia colored portraits. You don’t recognize the faces in any of the photos, but their elaborate top hats and bustle gowns evoke nineteenth century fashion. You turn it over to find a name unfamiliar to you, elaborately splashed across in fancy letters and intricate details. Your curiosity takes over and you begin to wonder, “what is this?”

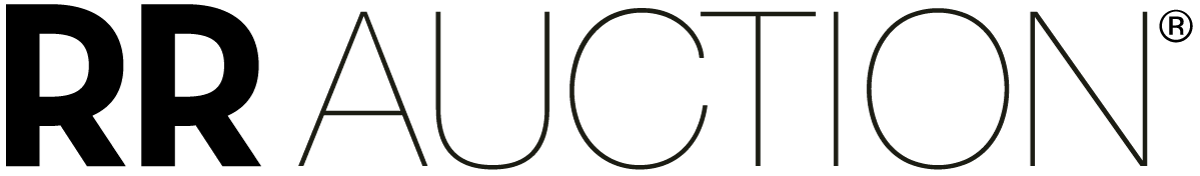

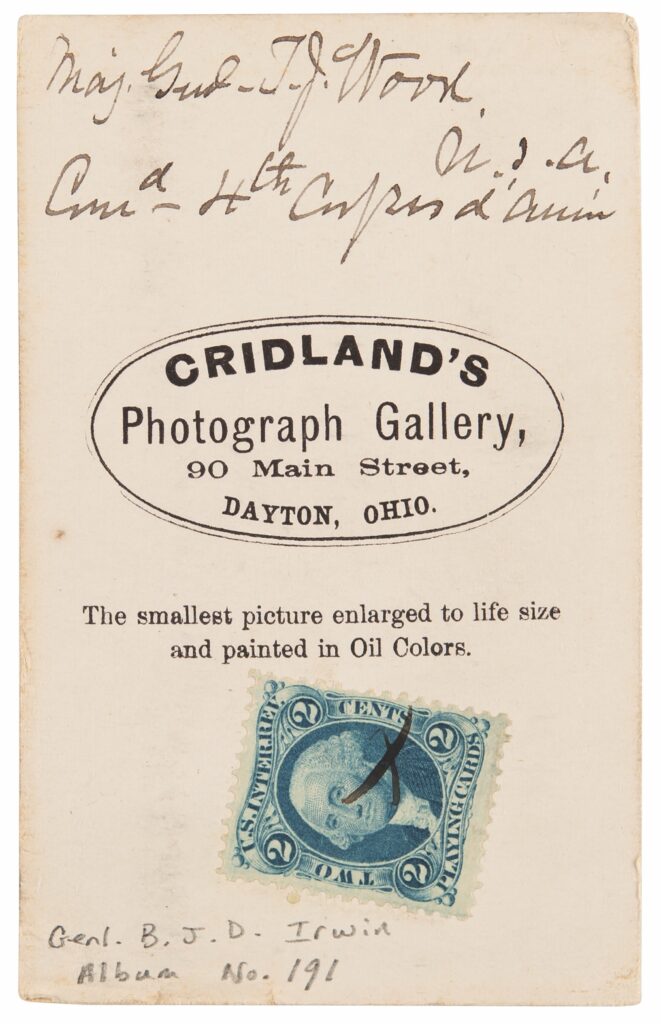

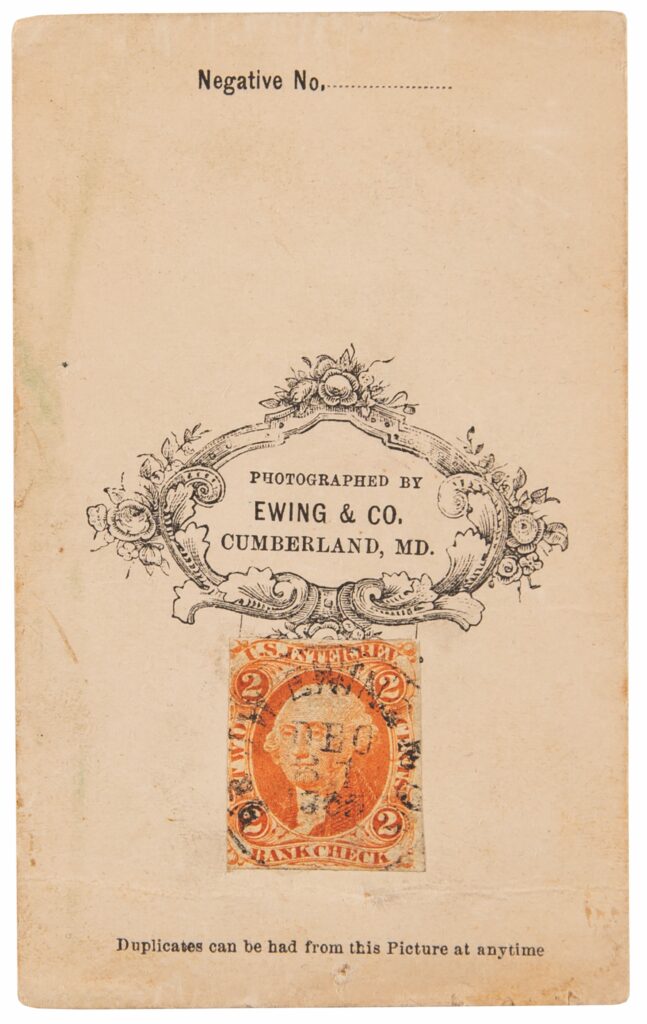

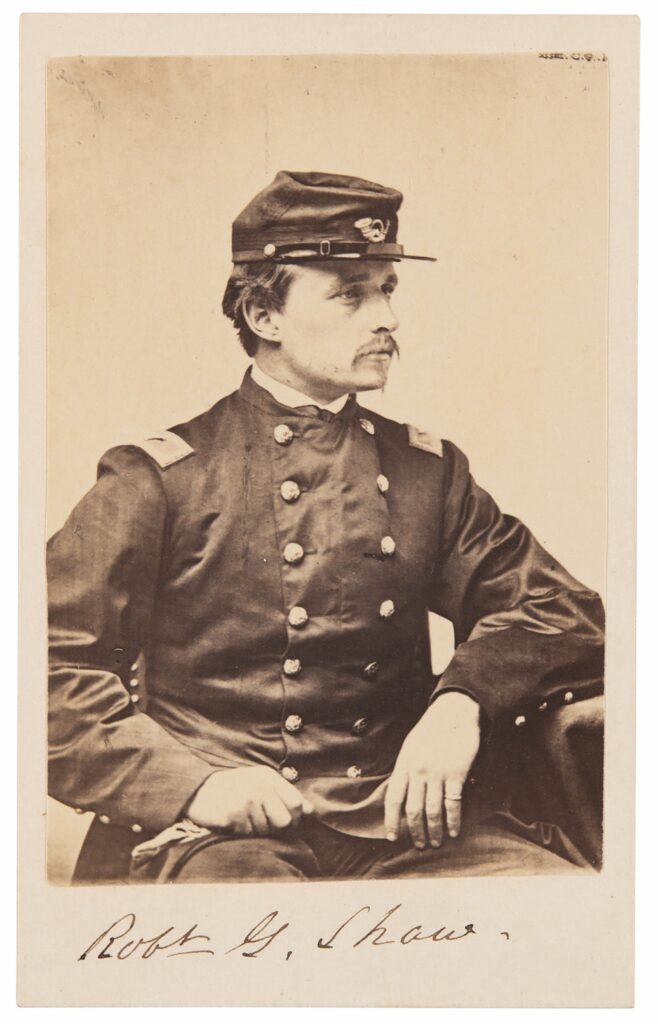

These pictures, called Carte-de-visites, were small pieces of thick paper mounted with a photograph, usually showing a single subject usually from the shoulders up (though not always). In addition to the photograph, the reverse of the carte-de-visites would be printed with the photographer’s name, address, and personal emblem.1

Prior to their creation, it was custom for people to leave calling cards when visiting friends and family, so much so that many houses had tables to receive the cards of visitors. Photographer Andrew Adolphe Eugene Disderi, sought to build on this custom (hence the name “carte-de-visite” which translates to “visiting card”), though it didn’t quite catch on for that purpose.2

“Cartomania”

When Disderi patented the format of the carte-de-visite in 1854, it started a brand new photography craze. Before this, professional photographers were accustomed to the process of daguerreotypes or collodion positives, but these photo processes came with caveats. Making and duplicating copies was often a hassle, and, in the case of daguerreotypes, were an expensive venture only available to the upper classes.3 The carte-de-visite process was a much cheaper alternative that could produce multiple copies of the same photo, so everyone could have keepsakes of their friends, family, and favorite celebrities (seems not much has changed!).4

The trend really took the world by storm when public figures started getting in on the fad. Emperor of France Napoleon III approached Disderi in 1859 to create a carte-de-visite to distribute to the public. Across the pond, J. E. Mayall captured images of British Monarch Queen Victoria, her husband, Albert, and their children and published his portraits in 1860. It wasn’t uncommon to find celebrity cartes being sold in shops at the time.

Dating Your Photographs

When you’re looking through your own family portraits, do you ever wonder when they were taken? It can feel daunting when your cartes lack handwritten dates. Examining the subject’s clothing is one way, but there is another method to help you narrow down a timeframe even further. Starting on August 1, 1864 and ending 2 years later in 1866, the government charged a tax on photographs, including carte-de-visites, called The Sun Picture Tax.

Tax stamps were usually affixed to the reverse of the photo, most commonly for 1, 2, or 3 cents. The monetary amount varied based on the cost of the photo, and each stamp could be further dated by their colors. 5 cent stamps were red, 3 cent stamps were green, 2 cent stamps were either blue or orange, and 1 cent stamps were red and were only in use from March 1865 to August 1, 1866.5 Though not a perfect pinpoint method, those investigating the history of their photographs can at least narrow dates down to a small stretch of time.

The Collector Craze

While they are now common flea market wares, you can find portraits of various famous figures for sale at auction houses across the globe. If you’re really lucky, you might find one that is signed by its notable subject – for a hefty price.

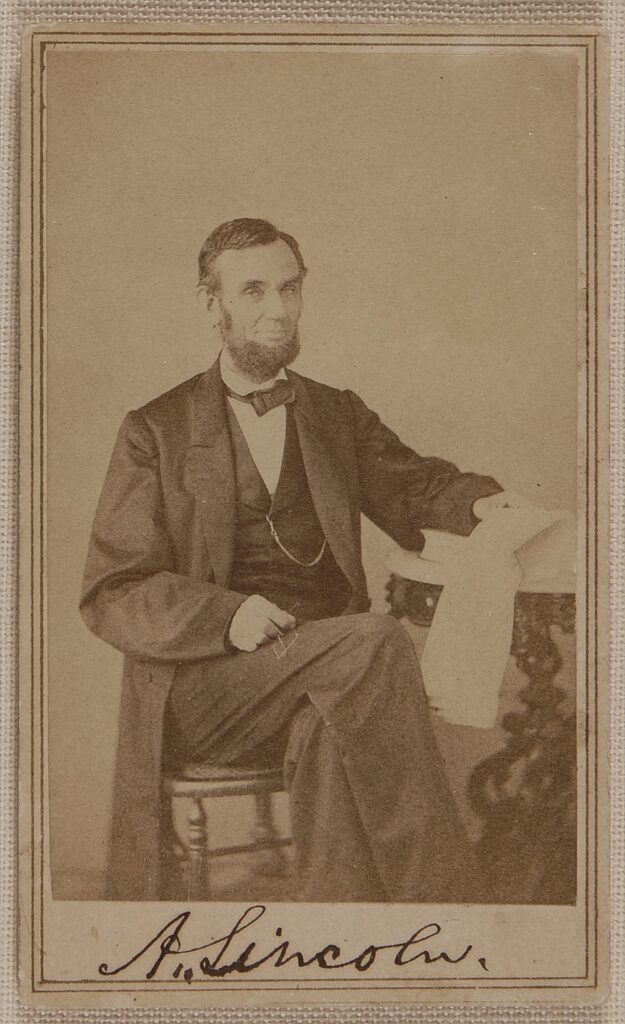

It’s that special addition that makes items like this Abraham Lincoln photograph all the more valuable, reaching a high price of over $90,000 when it sold at RR Auction in 2012. This photo was originally taken by Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner in 1863 while Lincoln was in office during a session which the president described as ‘very successful.’ And still, their popularity continues to grow. In 2022 a carte photo of Millard Fillmore signed amidst the Civil War sold for $12,079.

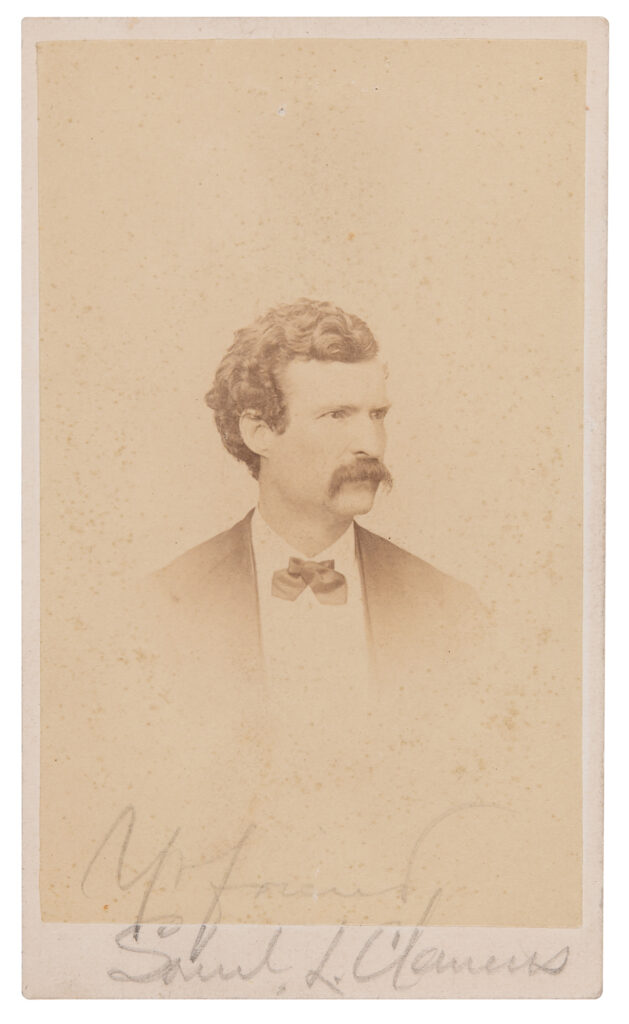

RR Auction’s July 2024 Art, Literature, and Classical Music auction presented a signed photograph from a celebrated author of classic literature. Samuel L. Clemens, better known to many as Mark Twain, had his likeness captured by E. P. Kellogg during his years spent in Hartford, Connecticut. Clemens moved his family to Hartford in 1873 and began work on an extravagant abode at 351 Farmington Avenue, just down the street from Kellogg’s photography studio. The house – now known as the ‘Mark Twain House’ – was described by Clemens biographer Justin Kaplan as ‘part steamboat, part medieval fortress and part cuckoo clock,’ and it was said Clemens spent some of his happiest and most productive years at the home.

Signed photographs of the wordsmith are of the utmost rarity since he is uncommon in this format. The Clemens photo reached a selling price of $2,805.

Carte-de-visites also found great popularity with the military. As keepsakes, families could hold onto images of their loved ones who had gone off to battle in the Civil War.6 Both Union and Confederate soldiers posed in uniform for their portraits, and military cartes, especially of famous generals, are also auction staples, often going for high prices. RR has seen its fair share of Robert E. Lee portraits. Signed cartes of the general typically go for thousands, with RR’s highest price realized being $9,981.

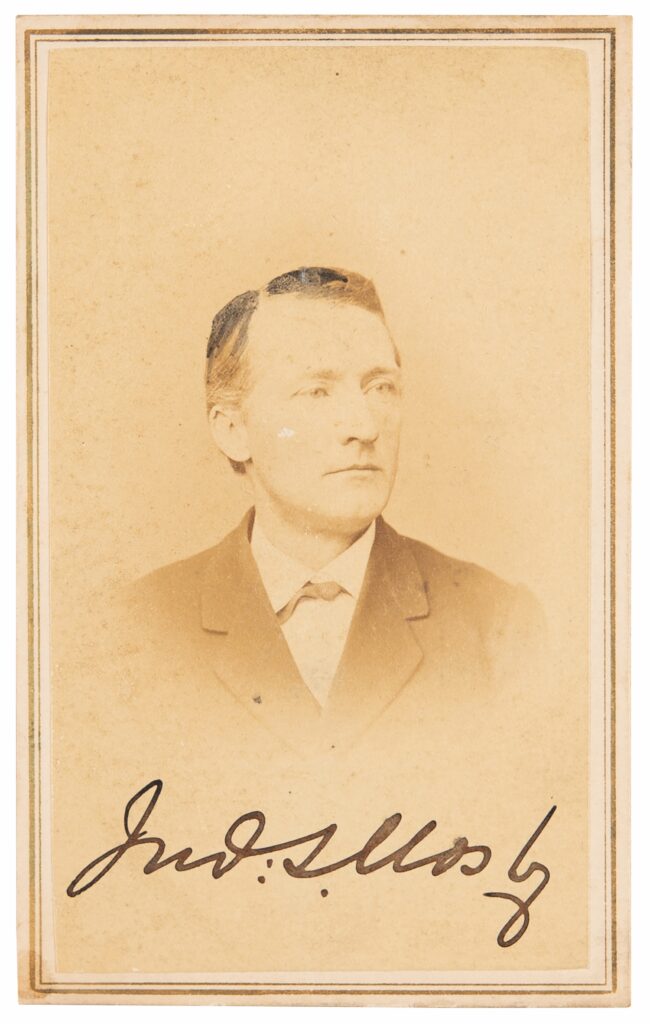

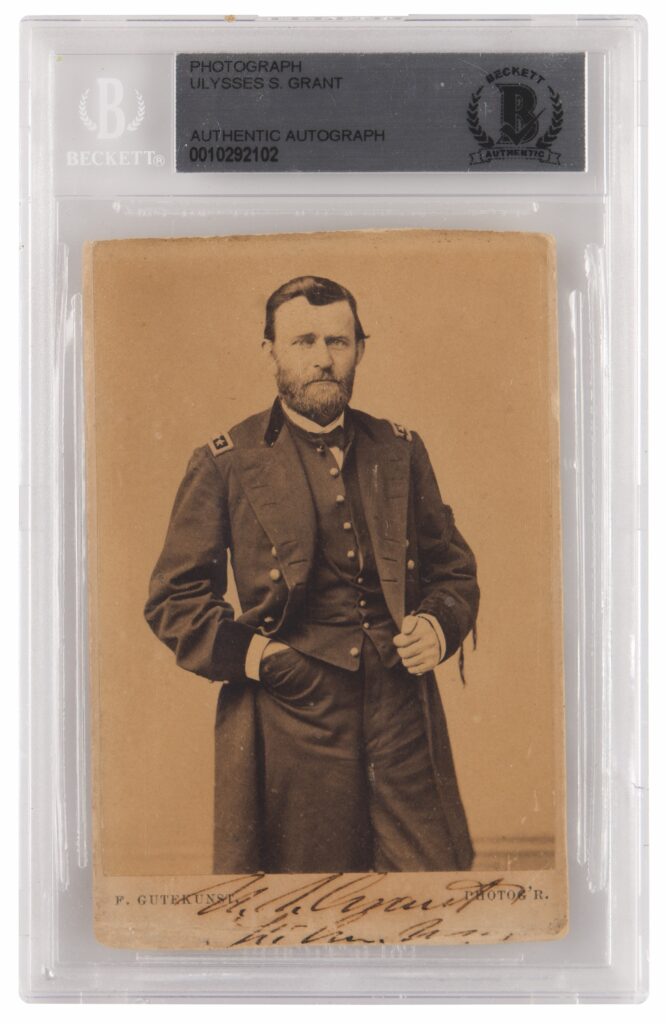

Their upcoming July auction, which puts a focus on the Civil War, presents several cartes depicting famous generals who fought in the war. Two photos of the lieutenant general U. S. Grant and the fabled ‘Gray Ghost’ John S. Mosby are expected to sell for around $3,000 each. The photo depicting Grant in military uniform was taken shortly after the assassination of President Lincoln, prior to his presidency in 1869. Another photo of Union officer Robert Gould Shaw, who commanded the all-black 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, is looking to reach $5,000.

In a world where intricate outfits and formal portrait sessions have been replaced with digital cameras and candid phone snapshots, the carte-de-visite and its rich history still stand on its own among collectors – a groundbreaking fusion of art and science.

Footnotes

- “Carte-de-Visite,” National Portrait Gallery. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/explore/glossary-of-art-terms/carte-de-visite. ↩︎

- Georgen Charnes, “Cartes-de-Visite,” Nantucket Historical Association, Accessed June 14, 2024. https://nha.org/research/nantucket-history/history-topics/cartes-de-visite-the-first-pocket-photographs/. ↩︎

- “Using and interpreting photographics sources,” The National Archives. Accessed June 18, 2024. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/students/working-with-photographs/using-and-interpreting-photographic-sources/. ↩︎

- Colin Harding, “How To Spot A Carte De Visite (Late 1850s-C.1910)” Science + Media Museum. Published June 27, 2013. https://blog.scienceandmediamuseum.org.uk/find-out-when-a-photo-was-taken-identify-a-carte-de-visite/#:~:text=A%20carte%20de%20visite%20is,either%20daguerreotypes%20or%20collodion%20positives. ↩︎

- Lisa Lisson, “How to Date Antique Photographs Using Tax Stamps,” Are You My Cousin? Genealogy. Published Jan. 15, 2016. https://lisalisson.com/how-to-date-photographs-using-tax-stamps/. ↩︎

- Isadora Chicoine–Marinier, “Collecting Cards: Carte-de-Visite,” National Gallery of Canada. Published Dec. 11, 2019. https://www.gallery.ca/photo-blog/collecting-cards-cartes-de-visite. ↩︎

Sell your carte-de-visite portraits at auction

Contact our team for a free auction appraisal