by Brooke Kennedy

Update: Indianapolis Colts Owner Jim Irsay revealed himself as the buyer of these Ford’s Theatre tickets that sold on September 23, 2023 for $262,500 in a segment with CBS Saturday Morning.

A pair of tickets to Ford's Theater for April 14, 1865, the night Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, sold for $262,500, and the winning bidder is a familiar name to sports fans. @MacFarlaneNews has more on the tickets' new owner. pic.twitter.com/Bl1FHpZrYU

— CBS Saturday Morning (@cbssaturday) October 14, 2023

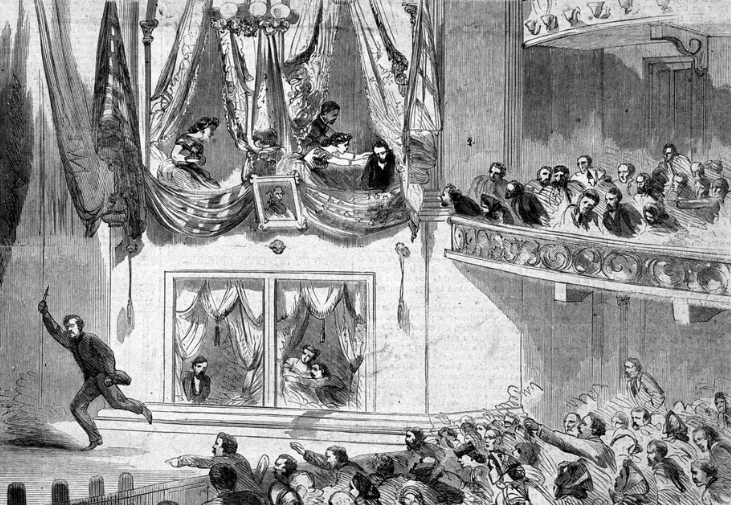

April 14, 1865 marks the tragic assassination of Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Audience members witnessed the assassin, John Wilkes Booth, as he jumped from the president’s private box down to the stage, shouting one final declaration – ‘sic semper tyrannis’ – ‘thus always to tyrants’ – before making his escape. Among the crowd were two ticket holders who had a clear view of these tragic events from their front row seats in the theatre’s dress circle.

Now, more than 150 years later those two tickets held by those witnesses will go under the hammer in September 2023 at RR Auction of Boston.

A Brief History of Ford’s Theatre

Before it became the scene of one of the most devastating moments in American history, Ford’s Theatre was a cornerstone of Washington entertainment.

Beginning its life as a house of worship in the early 1830s, acclaimed theatre manager John T. Ford purchased the building in 1861 to convert it into a theatre. After a few financially successful years, in 1862 Ford’s Theatre (then called Ford’s Athenaeum) caught fire with firefighters failing to quell the flames. Despite this setback, Ford set out to rebuild a larger, modernized structure. After several months of painstaking work, Ford’s Theatre re-opened in August 1863 with a successful production of “The Naiad Queen.”

The theatre would have another few fruitful years until its second closing on April 14, 1865, when President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated at the hands of John Wilkes Booth.1 Historians and collectors have long been fascinated with the events of April 14 – the planning, the aftermath, and the eyewitnesses. What would the day have looked like for a pair of ticket holders who attended Ford’s Theatre that fateful night?

Attending “Our American Cousin”

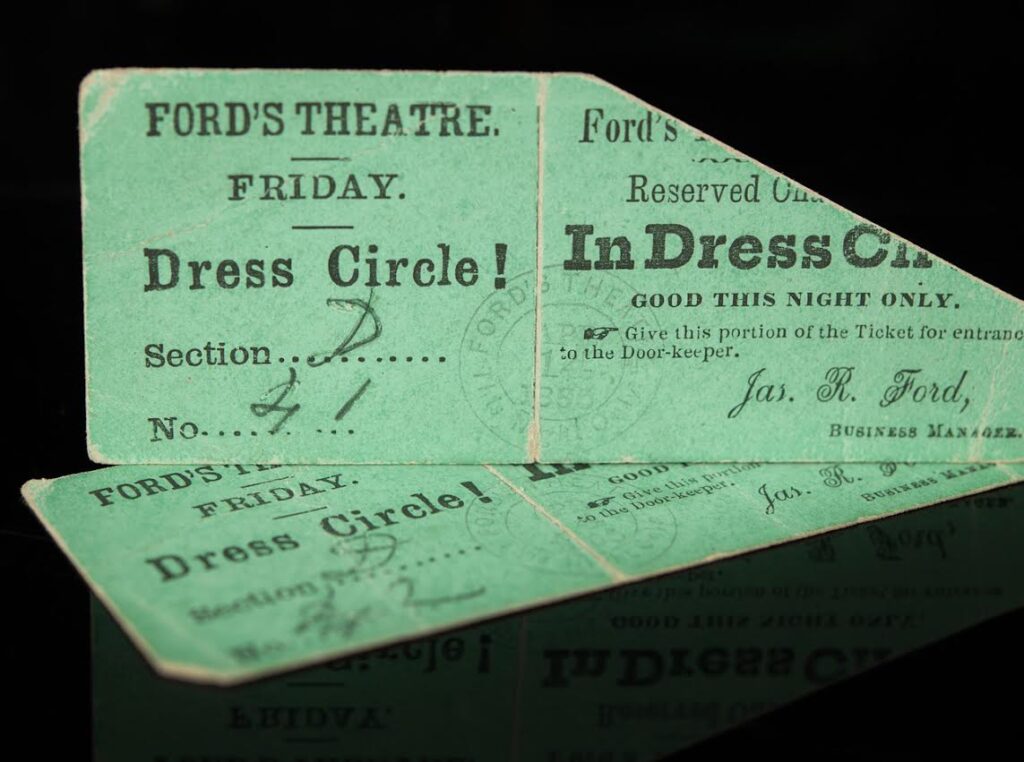

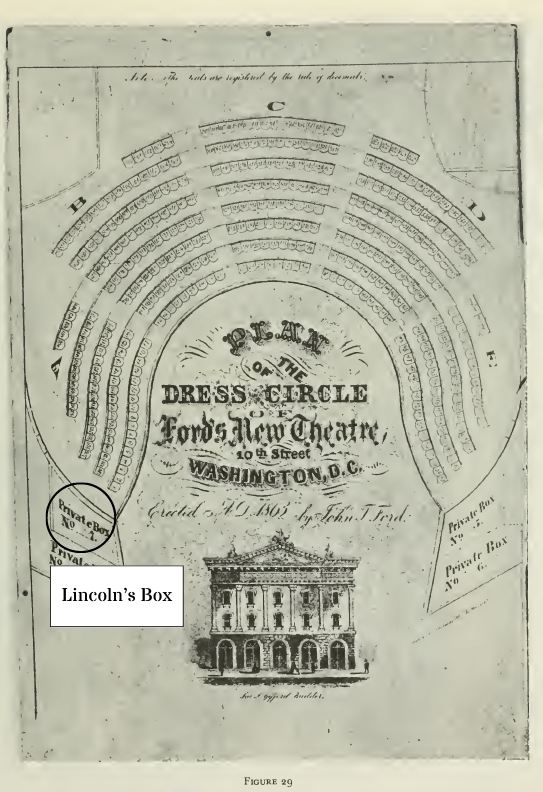

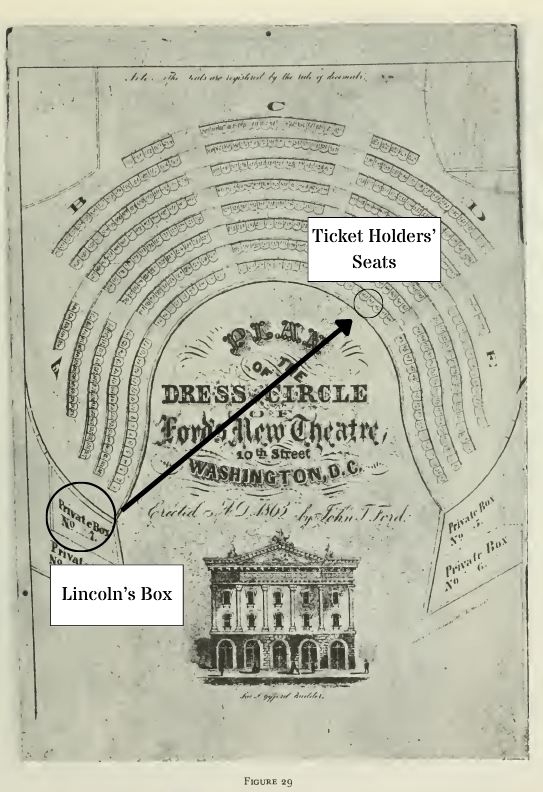

With Ford’s vision of a much larger space, guests were treated to nearly 1,700 seats, with 421 seats in the dress circle (first balcony) alone, and eight private boxes. And, compared to most modern theatres, the numbering of the seats at Ford’s looked very different. Starting at the front row of section A and ending in the front row of section E, the seat numbering would go across all rows in concentric arcs, beginning at number 1, and then number 2, etc. Ending at seat 60 in section E in the dress circle section, the numbers would continue into row 2 in section A and the numbers would proceed through each row as such. The orchestra section also followed this numbering system.

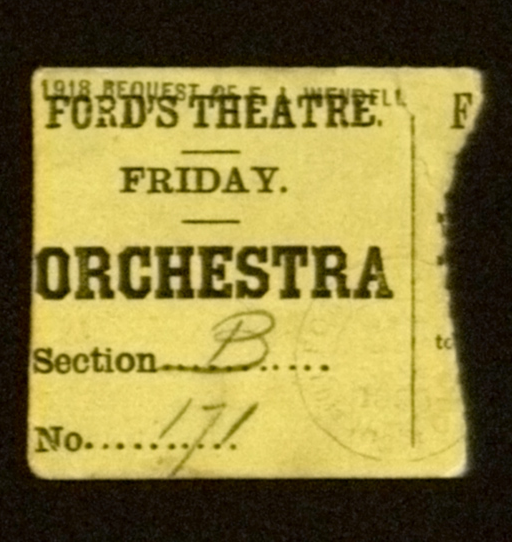

The seats would go all the way into the hundreds, as is seen on the above Ford’s Theatre orchestra ticket that reads, “Section B, No. 171.” This system is corroborated by the seating charts of the dress circle and orchestra above.

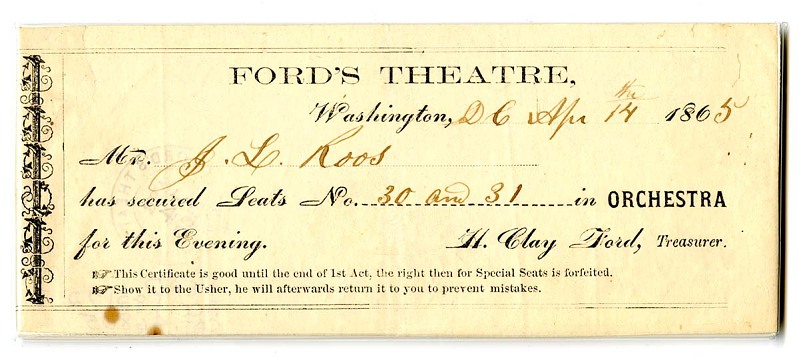

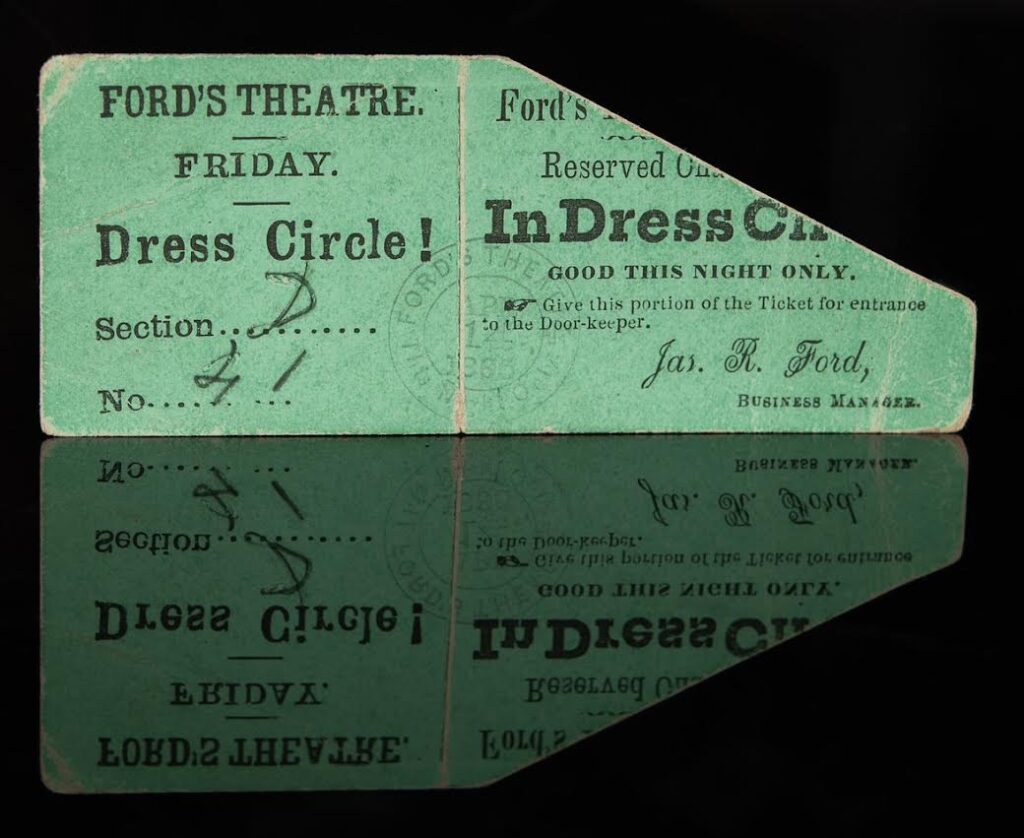

Along with its unconventional seating system by today’s standards, Ford’s Theatre’s box office offered patrons different types of tickets – Orchestra (lower level towards the stage), Dress Circle and Parquette (back of the Orchestra), and Family Circle (upper balcony).3 Customers could also receive advance tickets, like the one above, which featured the patron’s name, seat numbers, and the date of the performance filled out on the ticket by hand. These tickets were also stamped with the date of the performance. The Smithsonian example was presumably created prior to the performance date and not offered at the box office on April 14th.

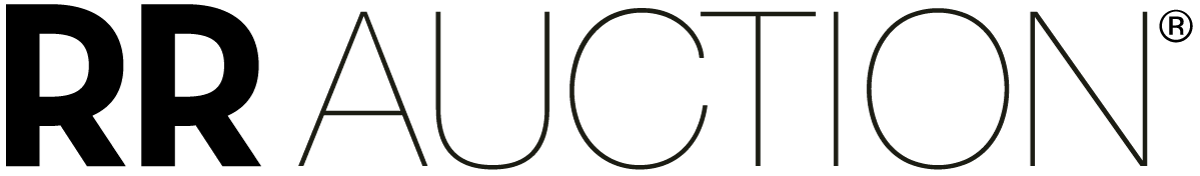

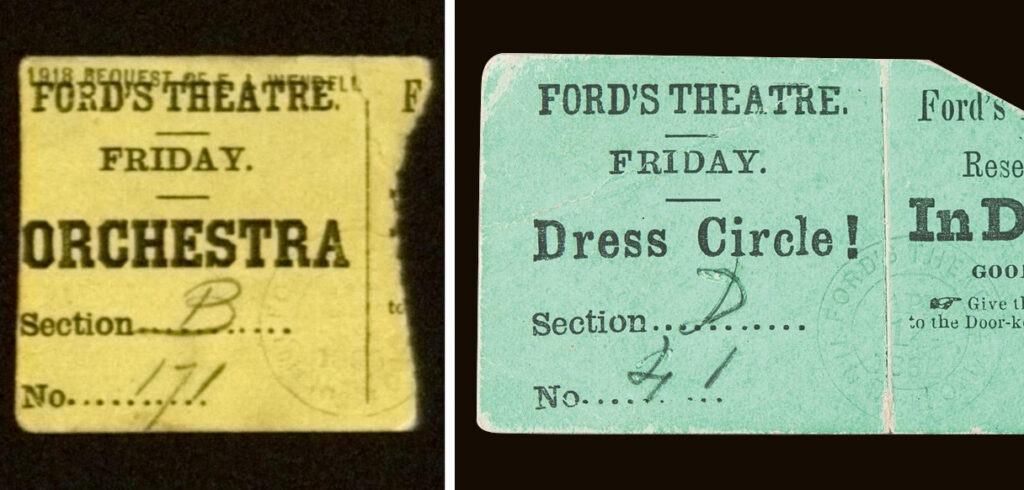

As evidenced by the Harvard stub, theatre-goers could purchase tickets that were stamped with the date of the performance they were sold for, and were valid for that evening only. The patron’s seat section and number would be written out in pencil on their respective lines. Both the Harvard example and RR Auction’s tickets feature this exact stamp showing the date April 14, 1865. And, the writing on all three tickets bear a striking resemblance to each other. These three Ford’s Theatre tickets are the only known examples to RR Auction to have been torn and have their seating assignments written on them.

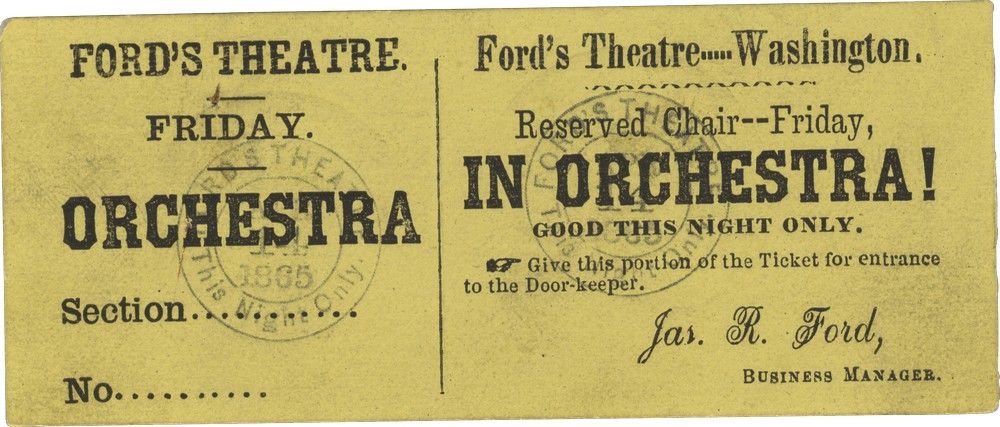

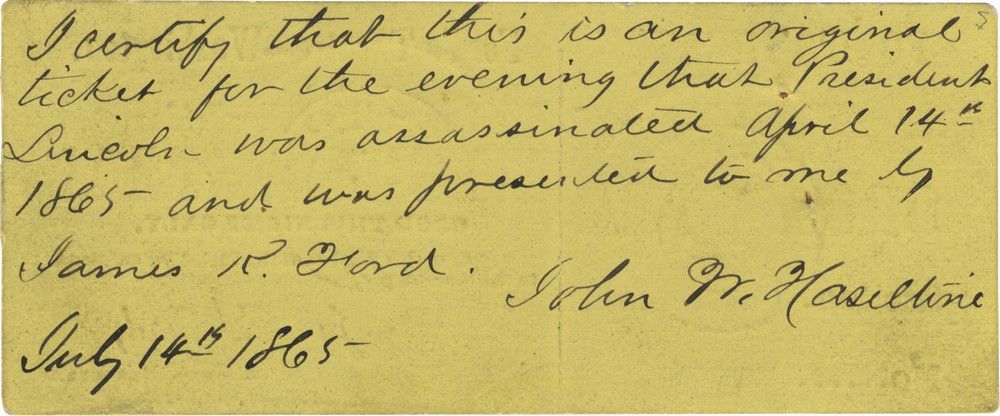

Furthering the notion that RR’s tickets were intended for the performance during which Lincoln was assassinated, an unused ticket for April 14, 1865 is pictured above – featuring the matching date stamps. A collector obtained this orchestra ticket on July 14th, 1865. After Lincoln’s assassination, the theatre remained closed for three months before briefly re-opening in July 1865, explaining the date written by the collector on the ticket’s reverse and the lack of a seat number. However, unlike this ticket example held by the Manuscript Foundation, RR’s pair shows signs of being used by their playgoers. Because Ford’s Theatre would remain closed for over 100 years, no other tickets were ever produced for future performances.

The right corners of both tickets are missing, indicating that they were presented to the ticket taker and clipped to confirm their admission. Annotated in pencil are the section – section D – and the seat numbers – 41 and 42. Looking at the dress circle seating chart, these ticket holders would have sat in the front row of the dress circle. Also, the Dress Circle tickets offered have a heavy crease through the date stamp when compared to the unused ticket.

Eyewitness Accounts

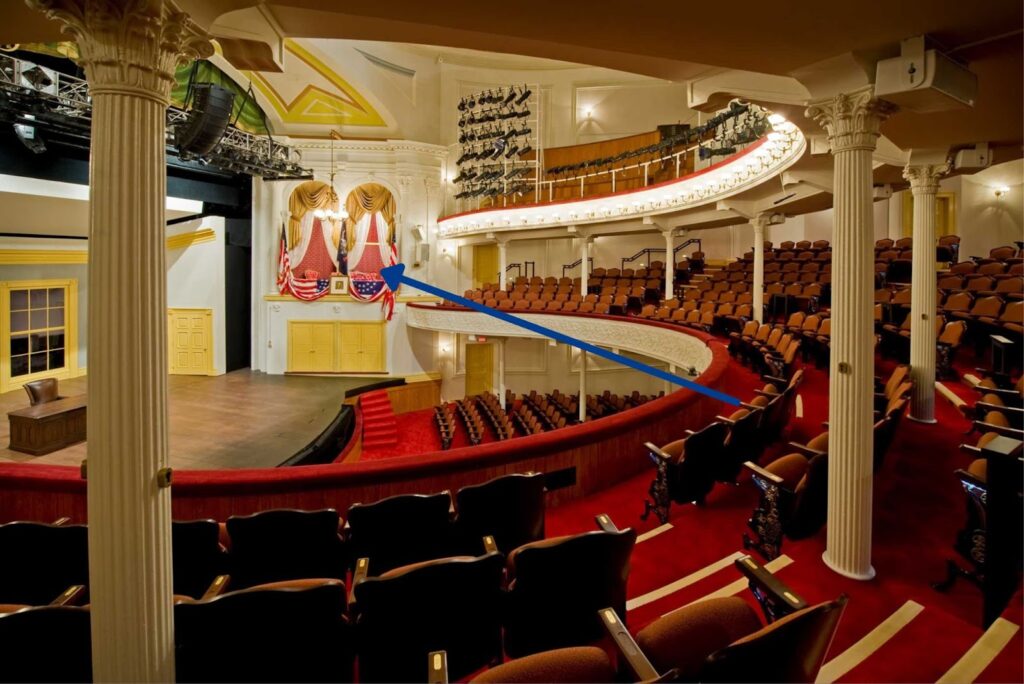

With the theatre crowded with audience members, many bore witness to these harrowing events – including the two ticket holders. While the playgoers would not have seen the exact moment of the assassination, based on the seating chart, they had a front row seat to Booth’s dramatic escape as he leapt from the box to the stage below.

Countless publications detailed what happened following Booth’s entering of Lincoln’s box.

“During the third act, in which there was a temporary pause for one of the actors to enter, a sharp report of a pistol was heard,” wrote The Burlington Times4 in their account. “A man rushed to the front of the President’s box… and immediately leaped from the box which was in the second tier.”

Borrowing a quote from his favorite Shakespearean character, Brutus, Booth reportedly shouted, ‘sic semper tyrannis’ – ‘thus always to tyrants’ – before fleeing the scene. Lincoln was removed from the theatre to the Peterson House across the way, where he died in the early hours of April 15.

History Heads to Auction

In September 2023, this pair of tickets will be heading to auction during RR Auction’s live Remarkable Rarities event, and the chain of custody is quite interesting.

Before making their way to RR, these tickets were originally part of the collection of famed collector Malcolm Forbes, also known as the founder of Forbes magazine. They later went to auction at Christie’s as part of their Forbes Collection of American Historical Documents on October 9, 2002, where they sold for $83,650.

For the first time in 21 years those two original tickets will go to market once again. In addition, no other authentic used Ford’s Theatre tickets from the night of the assassination have been to auction since the Christie’s sale. Only a handful of authentic tickets from April 14, 1865 are known to exist, making the reappearance of these tickets a huge moment in auction history.

Footnotes

- Stanley W. McClure, The Lincoln Museum and the House Where Lincoln Died (Washington. D. C.: National Park Service, 1949), pg. 3. ↩︎

- Norman Gasbarro, “The Architecture of Ford’s Theatre & Laura Keene,” January 23, 2012, https://civilwar.gratzpa.org/2012/01/the-architecture-of-fords-theatre-laura-keene/. ↩︎

- “Frequently Asked Questions: Ford’s Theatre,” National Park Service, August 15, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/foth/learn/historyculture/faq-fords-theatre.htm. ↩︎

- George and Lucius Bigelow, “Presid’t Lincoln Assassinated,” Burlington Times (Burlington, VT), April 15, 1865. ↩︎